Just over two years ago I was a proud Ulster University student, freshly graduated from my Masters in Multidisciplinary Design. While many other students were worrying about finding a job, my co-founders and I had just signed a venture capital deal that valued Get Invited at over $1 million.

Get Invited was our Masters project.

This is the story of how we started Get Invited, and also a guide to building an investable $1 million company, I also hope it will enlighten and inspire students about the fantastic entrepreneurial opportunities that exist while at university or college.

Many people don't seem to realise this, but university is actually the ideal place to start a company.

Why?

- Free office space

- Access to talent

- Mentoring

- Access to computers and equipment

- The perfect place to find a co-founder

- Access to knowledge

- Financial support (grants and investments)

What more could you want?

In addition to exploiting all of these opportunities:

- I spent seven days at Stanford University in California receiving mentoring from billionaires like Vinod Khosla and David Filo, and it didn't cost me a penny

- We received a £3,500 grant to fly to a conference and demo Get Invited

- We got mentoring and assistance writing our business plan for investment

- Ulster University bought shares in Get Invited

How did we do it?

Raising money from investors and building a $1 million company is by no means easy, but it's perfectly achievable. If we managed to do it as students with absolutely no business experience, then anyone can do it.

I believe our success was down to three things:

- Product

- Team

- Customers

You need to nail all three of these to start a business, and to raise investment. Of course, there are exceptions – if you have a killer product, but no team yet – you'll still be able to raise money but your chances are significantly higher if you can demonstrate that you have all three components.

1. Product

I cannot emphasis how important having a product is. I hear so many people complaining that they can't get their idea funded.

No-one (particularly an investor) cares about your idea, they care about execution. Everyone has an idea but only a very small fraction of people can execute. Even less can see it through and sustain momentum of execution.

We spent almost 2 years building Get Invited before we were in a room with an investor. This timeframe should usually be much shorter, but we were also working on 5 other products at the time alongside consulting and lecturing.

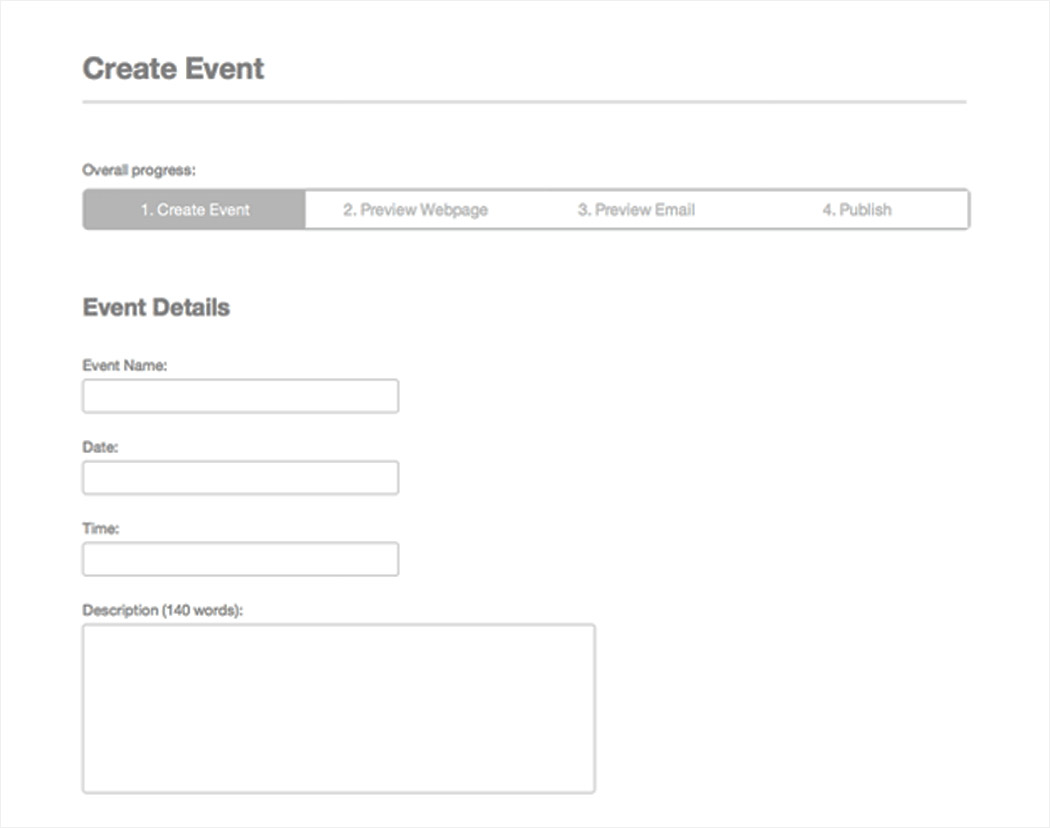

Building a product is not as difficult as it might sound. If you've spent weeks writing a development plan and feature roadmap that's going to take 6-12 months to deliver then you're doing it wrong.

We built the first Get Invited prototype in just 4 hours.

That's right, 4 hours. We sketched the user interface onto some large sheets of paper over lunch and then coded up a prototype in the afternoon.

Did it look great?

It looked like a website from 1994 viewed on a black and white TV.

The important thing is that we built something and then identified our first potential customer. This was a gentleman called Tim Kerr, an event organiser within our university who ran the annual Ulster Festival of Art & Design (again, we used the connections available to us within university).

We set up a meeting with Tim, asked him a list of questions about the system he was currently using and showed him what we were working on (the god awful prototype). He provided us with a huge amount of valuable feedback about the problems he was currently having and what his ideal ticketing system would look like.

We then went away and started building an alpha version of Get Invited based on Tim's feedback.

2. Customers

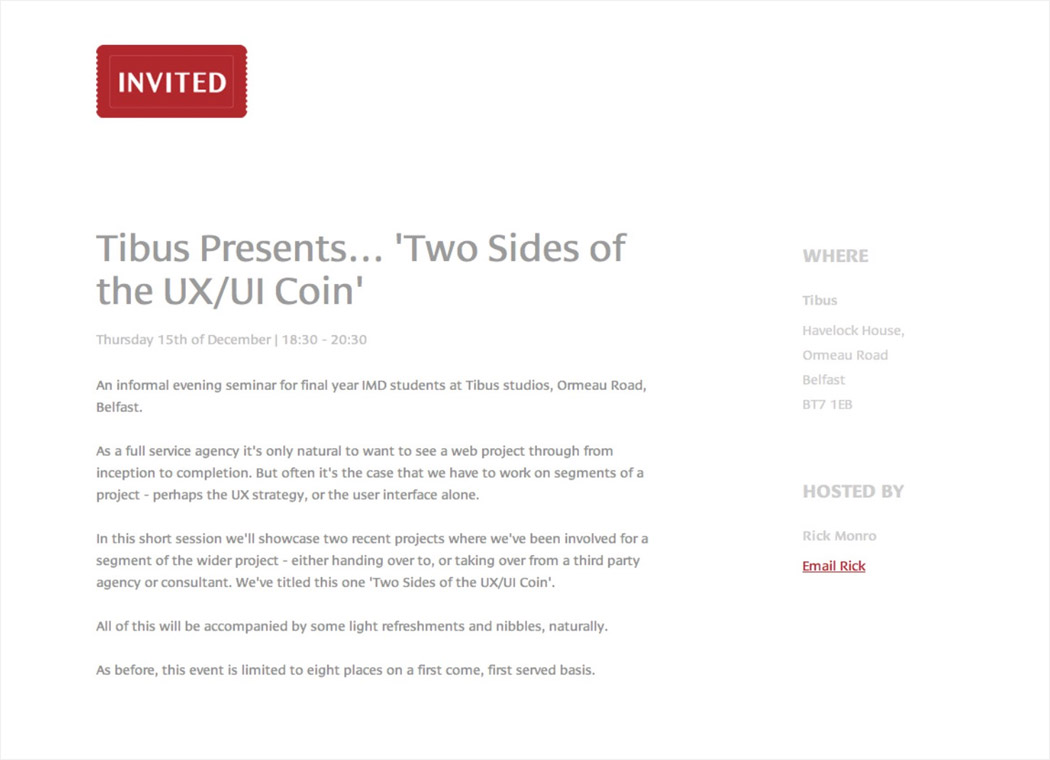

Four weeks into development, we identified another local customer, Rick Monro – who was organising design events for Tibus (UTV's design subsidiary) at the time.

Rick agreed to try Get Invited, so we set him up with a user account and he ran his "Two Sides of the UX/UI Coin" event with free tickets. Our first customer!

So, to re-emphasise, because this is important – after just 4 weeks of development, we had our first customer running an event on Get Invited.

I'm not trying to suggest that we were some kind of super-human product team that moved at the speed of light.

I'm suggesting that you only need to develop the most basic, crude version of a product that you can get away with initially to test it out with some early customers and get feedback to inform subsequent iterations.

Payments? We can do payments

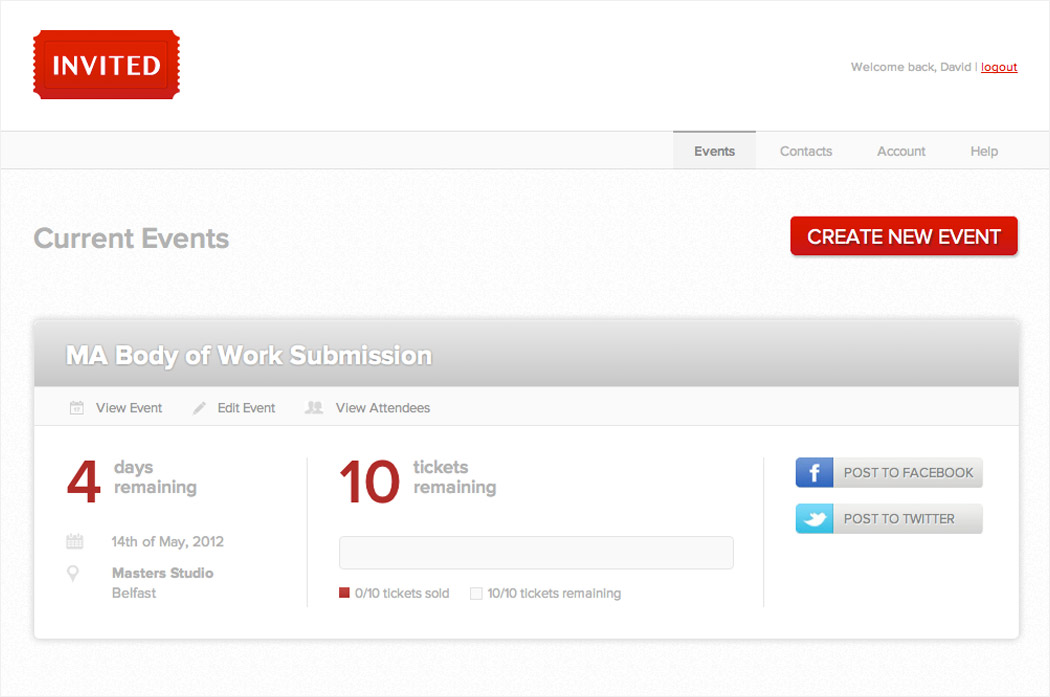

Just three months later, Tim Kerr approach us about running the 2012 Ulster Festival of Art & Design on Get Invited.

There was just one problem – we had no payment system and it was one week before the event launched. How the hell were we going to sell tickets?

A week turned out to be just enough time to build a very crude payment engine using PayPal.

The whole thing was a semi-legal operation on our part that was literally hanging together with virtual sellotape.

Obviously, this was an incredibly high risk manoeuvre, but we had built up a good relationship with Tim and we were on hand 24/7 to monitor the system and make sure nothing went wrong.

Thankfully, it all worked perfectly. Tim was delighted and we were receiving lots of positive feedback from ticket-buyers, stating how simple it was to buy a ticket on Get Invited.

Result! We sold just over £10,000 tickets in a few weeks. Every moment of that time was pretty scary, but we now had a functioning product, validated in the real-world with real customers.

The user interface looked a lot better at this stage, but in hindsight it was still pretty bad.

The path to revenue

Our PayPal system could just about process ticket sales, but it wasn't sophisticated enough to charge a commission on transactions and generate revenue for Get Invited. We didn't even have a bank account.

What we did have though, was the foundation of a business model. We knew that someone was prepared to process payments through Get Invited, and we knew that with a proper payment processor in place, we'd be able to take a commission on each transaction.

If you don't have revenue at the time when you're raising investment, you will at least need to demonstrate that you know how you're going to make money.

3. Team

The final piece of the puzzle was that we had a team in place – the three founders. David was another student in my class, and Chris was our lecturer. Unique setup, I know.

Both David and myself were able to build the product and Chris was good at hustling to get our early customers onboard and spread the word about Get Invited.

We had a major advantage in that we had David in place as a CTO from day one. I know many solo founders are struggling to find a tech co-founder and it's so important to have this person onboard early to deliver the product.

There was still one massive problem though.

We didn't have any experience running a company, and once we'd figured out the roles of each founder; as the new CEO of Get Invited, I had absolutely no idea what I was supposed to do.

I had zero business experience. In fact, my first attempt at a startup failed because I was literally terrified into paralysis over my lack of business knowledge.

It turned out, that this wasn't such a huge problem for Get Invited after all.

The Big Pitch

Two weeks before David and I graduated, we were in a room pitching to a local investor for £100,000.

At this point we had put in a lot of man hours working on the product and writing a business plan. We'd been through multiple product iterations and now had a stable platform. We had also scaled our customer base slightly and attracted a few new customers through word of mouth.

In addition to having the product, team and customers, there were another two things I attributed to our success on the day.

- Honesty

- Support

1. Honesty

On the day of the pitch, I delivered a confident, compelling and well rehearsed 7 minute pitch to a room full of investors and 50 spectators – all of whom were highly experienced entrepreneurs acting as advisors to the investment committee.

I showed a wonderful demo of the product, highlighted that we had some customers and gave an introduction to each team member. I thought it went really well.

Wrong.

What happened next totally destroyed me. An onslaught of questions ensued, and not a single one that I could answer. It was crystal clear that I hadn't a clue what I was talking about or had the faintest idea of how to build a business.

Rather than try and bullshit my way through it, I was open and honest about our lack of experience.

It was a wise decision. The people who had ripped me apart during the Q&A? They all approached us afterwards and offered to help us in any way they could.

Our investor later told us that during their committee meeting, everyone in the audience had been massively supportive of us and put their recommendations forward that they proceed with the investment.

I put this down to the fact that we seemed like decent people because we were aware of our weaknesses and we were honest about them. Investors invest in people, after all.

It's absolutely fine that you don't have all the answers you need, people will respect you so much more if you just say that you don't know – rather than pretend you know everything, because no-one likes a smart-arse.

2. Support

Lack of experience from the founders is a risk for any investor and we knew this. One of the ways in which we mitigated this risk was by demonstrating that we had support behind us.

Another great benefit of being students was that we were able gain support from Ulster University and could demonstrate this in our pitch.

This wasn't just some pie-in-the-sky camaraderie in which Ulster University were cheering us on from the sidelines.

They had committed to make a financial investment in Get Invited, so we were pitching to investors with a percentage of the round already committed. This provides enormous validation for the other investor and makes closing a deal much easier.

We were also being mentored by Tim Brundle, the CEO of Innovation Ulster, which is Ulster University's investment vehicle. Tim is highly experienced in growing technology companies and is also very well respected in the local community, so having his support helped us establish credibility and demonstrated that we were plugging the experience gap.

In the end we received an offer for £200,000, which was double what we had asked for and then we settled for £175,000.

Our investors knew we were inexperienced, but being open and honest about this built trust and we also showed the initiative to find support, and the determination that we would do whatever it takes to make Get Invited a success. This enabled us to go from pitching to a signed term sheet in a matter of weeks.

Of course, this was in addition to having the product, customers and team of course.

Conclusion

There are two lessons here – if you want to build a company and raise investment, then you need to make sure you're focused on the three key areas:

- Product

- Customers

- Team

Forget about writing business plans and spreadsheets until you have these three things nailed. A business plan is just another idea, it means nothing unless it's been executed or you can demonstrate that you have the ability to execute it – and you can only do that through your previous actions.

The other lesson is less known, and it's that university is a fantastic place to start a company, and I strongly encourage every student to seriously consider entrepreneurship as a career opportunity.

I've been fortunate to walk straight out of university into a career where I have total freedom doing something that I love, while travelling all over the world and working with great people.

Did we do anything that others can't? No. We just worked hard and made use of the opportunities that were available to us in university, and a large part of that opportunity was using the time to build something worthwhile that had commercial potential.

Those exact opportunities are available to every student, don't miss out!